The numbers amaze. Economies stopped and now as we get new data coming off such a pulverised base, the percentage growth numbers can dazzle on the upside. This can take forecasters by surprise – recent jobs numbers in the US are a good example, as are UK retail sales.

Economic growth is a good thing – very good. But hard as it might be, the focus needs to be on the quality of that growth as much as the quantity.

On issues such as sustainability or climate change, this does seem to be taken on board. There is a clear green tinge to many public investment initiatives. Governments have been made aware of the demands of the public, especially the younger cohort, for a clear green agenda in practically all sectors. The Swedish government’s attached conditions, regarding carbon emissions, in a recent financial injection into the airline SAS, are an example of how the emergence from the pandemic will have a greater sustainability imprint.

However there is another aspect where we need to be vigilant and that is the issue of income inequality.

Inequality in income distribution in countries and across countries already was a severe and growing problem. There are clear social consequences from the trend. But the other aspect of this is that quite simply it slows economic growth, leaving permanent scars.

Every pandemic in the twentieth century has led to increased income inequality.

Covid-19 has disproportionately hurt disadvantaged groups. While many people have been adversely hit by the health emergency and government mitigation measures, those with a lack of savings or insurance are impacted the most by a sudden loss of income. Workers in the informal economy with weaker job attachment or those in low skilled service sector occupations also bear brunt of the lockdown. In the developing world employment numbers for those with only basic skills fall by 5% over a 5 year period after a pandemic according to the IMF. Higher skilled workers and those with advanced education fare much better.

Educational prospects are severely impacted by the global lock down. The United Nations estimates that more than half a billion children have lost their access to education through this period. Lack of internet access and lack of appropriate devices is a significant factor in this, and according to the UN, Primary school children have been most impacted. While a concern globally, with potential long term consequences, it is especially a problem for emerging economies who face higher levels of “learning poverty” – an inability to read or understand a simple text by age 10.

Another feature of income inequality is that many people and indeed small companies don’t have full access to financial services and technology. Limited access to credit increases vulnerability both at individual and company level when cash flow simply stops. This leads to job losses and business closures which turns further widens the gap.

History shows that the greater the pre-existing inequalities, the more uneven is the impact of the pandemic. Income equality will hold back the strength and durability of growth.

In some countries the early experience isn’t great. In the US many of the financial measures aimed at lower income groups are set to expire in August – with little appetite from Republican politicians to extend. On the other hand a lot of tax breaks and provisions favour the already wealthy – according to a Congress Committee, 82% of those who stand to benefit earn at least $1m. annually.

We need a more inclusive recovery.

It is good that governments around the world have deployed extraordinary measures swiftly and will continue to do so, but the shape of that investment matters if we’re to prevent long term scarring of the global economy.

Healthcare and social protection need to be high on the agenda if we are to prevent the mistakes of history. Education needs investment with a view to ensuring wider access to the digital classroom. Failure here may cast the longest shadow. Access to high quality childcare must expand, which in some cases may boost female participation in the labour force and ultimately long term growth. It will be important to harness the power of technology in other areas as well as education. Financial inclusion can matter. If we broaden the access of low income households and small businesses to finance, it may be possible to smooth the experience during a cash flow shock. The IMF estimate that there can be a 2 to 3 percentage point difference in GDP growth over the long term between financially inclusive countries and their less inclusive peers.

Education, health-care, social protection, and technology should all be points on the compass as we navigate a path out of the down-turn. It would be important that there is co-operation and cohesion within and between regions. Policy measures, where they can, should be concerted and consistent.

That could be the challenge in a world where borders and minds may be closing.

Note: This article first appeared in the Sunday Business Post.

Investors need to find a balance between short term and long term factors in making decisions.

Investors need to find a balance between short term and long term factors in making decisions.

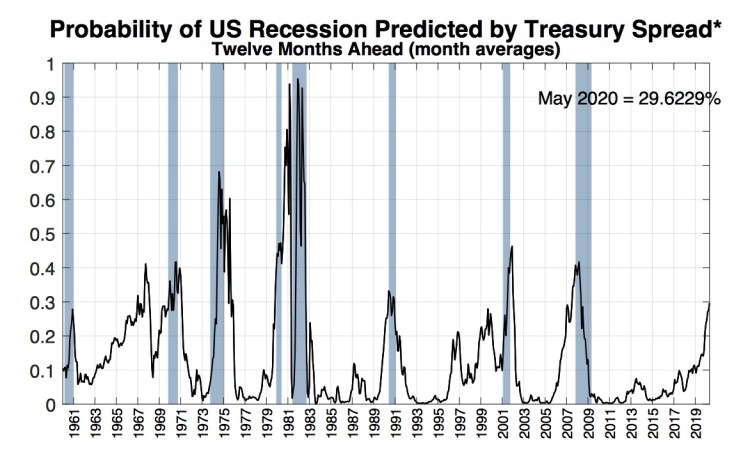

So, despite its pedigree the inverted yield curve may not be getting the universal acceptance it thinks it should merit. Why might it have lost some of its power?

So, despite its pedigree the inverted yield curve may not be getting the universal acceptance it thinks it should merit. Why might it have lost some of its power?