Talk of the end of Globalisation seems everywhere.

Tanaiste Michael Martin and Ursula Von der Leyen, European Commission President, have both spoken recently about “de-risking” our trade flows.

More extreme views believe that current global trade trends point to the end of Globalisation. The Peterson Institute sees Globalisation in retreat, and in its place they talk of “slowbalisation”

This matters because such an outcome could mean a major negative headwind to Global Economic growth over the next 5, 10, 20 years.

Much of this pessimism comes from looking at trade flows – aggregate world trade data relative to world GDP.

It’s true this trade data did soften around 2020 – which is exactly what you would expect in a world of pandemic and locked-down economies. The last two years have seen much talk of broken supply chains and massive trade disruptions due to the Pandemic and then various conflicts.

However improvement has been swift. If we look at more timely and dynamic surveys, we can see this. The New York Federal Reserve index, which tracks global supply chain pressure, now points to a largely normalised global trade picture. This clear improvement in physical trade is backed up by the noted Kiel Institute trade data.

Perhaps we’re not back at the pace of the growth in the “Golden Era” of global trade between 1970 and 2008, when corporates rushed to set up new supply chains.

But trade alone seems like a narrow enough gauge to capture the connectivity of the Global Economy.

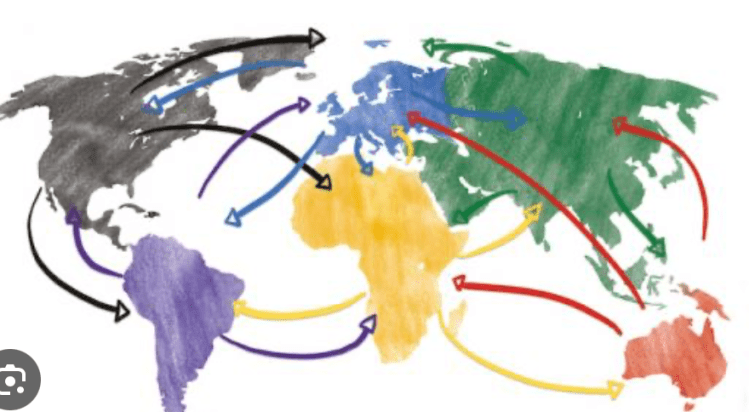

Given the importance of capital flows in the world economy and the ever increasing feature of human flows, a more holistic gauge of “Globalisation” would be in order.

The DHL Global Connectedness Index considers trade, capital, human and information flows. This much more comprehensive measure of Globalisation continues to push to new highs, and is well above its pre-pandemic level. Trade did take a bit of a knock in 2020 but has been on an upward trajectory since. In mid 2022, the volume of world trade in goods was 10% above its pre-pandemic level. The biggest blow (no real surprise) was to the movement of people, as the world closed in.

But it’s not business as usual. There is evidence of decoupling between the US and China, reflecting heightened geo-political tension between the two blocs.

Another key trend is what looks like a pick-up in trade within regions. Today roughly half of all international flows happens within regions, and this has been on an upward trend over the last 10 years. In a world of “near-shoring”, there is scope for this to grow.

Global trade will continue; even in what may appear a less benign world.

Michael Martin and Ursula Von der Leyen talk of de-risking – not decoupling.

And there is a sensible need to reduce risk in strategic sectors such as semi-conductors or critical minerals. G7 Finance Ministers have also spoken of the need for supply chain “diversity” where they may focus more on emerging economies to supply components and materials.

As regards capital flows, foreign direct investors will also continue to have a global perspective on their potential locations. But it may be a more risk aware perspective which some have described as a “China plus one” strategy, where they keep making things in China, but also have a back-up, for example Malaysia.

But trying to move production takes longer than we might think. A US Chamber of Commerce survey showed that 70% of US companies who manufacture in China have no plans to move in the next three years.

Undoubtedly, the shape of, and patterns within, global flows are changing. While western leaders look to de-risk and unbundle their trade with China, others like Bangladesh and Thailand are pivoting their economic future towards China. Indeed the World Bank sees this as the natural outcome of increased US/China tensions.

Globalisation has survived through wars and periods of protectionism. Now in the face of war and pandemic it continues to move ahead, though pace and patterns may have changed.

Heightened geo-political uncertainty serves to reveal the fragility of Globalisation.

Rumours of the demise of Globalisation have to date been unfounded.

The World Bank has rightly warned about the risk of fragmentation.

The greatest threat to globalisation, which we know has a beneficial economic outcome, may be complacency.