Interest rates are the policy tool of choice for Central Bankers.

And until the Great Financial Crisis, they were almost the only tool investors paid any attention to.

This was how Paul Volcker, then chairman of the US Federal Reserve, whipped inflation out of the US economy from the early 1980’s. Setting interest rate policy was how newly independent central banks were able to align their inflation goals with the business and economic cycle, as opposed to the electoral cycle which may have suited politicians more.

Monetary policy, with all its lags, was still how policy makers responded to the LTCM crisis and the early stages of the Great Financial Crisis.

However we have now grown accustomed to the unconventional becoming conventional.

Tools such as asset purchases are now a core part of the Central Banker’s armoury.

Partly this is a result of just how much the interest rate lever has been applied. In 1979 interest rates in the UK were 17% compared to 0.1% today. We are at, close to, or below zero in so many major economies.

And now the issue becomes apparent – can more cuts to interest rates work?

This issue is known as the “Zero Bound”. Pushing rates much lower will not stimulate the economy in “minus land” as it would in more normal circumstances. Interest rates cannot continue to go negative – investors would simply opt to hold cash – notwithstanding security and storage issues. Minus rates also undermine the banking system as an unwillingness to pass on negative rates to the retail base hits profitability. This ‘Zero Bound” issue with negative interest rates reduces their effectiveness as a Central Bank weapon.

So if rates can’t go down – can they go up?

Deep down in their monetary soul, central bankers like higher interest rates – simply because it allows them to cut rates if required to boost the economy. It is about keeping their powder dry.

The problem today would be the journey to those higher rates. A defining characteristic of the global economy and global corporations today is the sheer level of outstanding debt.

Government debt, even pre-Covid, had been high; but increased spending and lower tax income has pushed it even higher. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) in the US expects government debt to go to 200% of GDP by 2050. In the UK, similar forecasts, from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) are for public debt to go from £2 trillion to £3 trillion by 2025. Other European economies are even more indebted as are a large number of Emerging Economies.

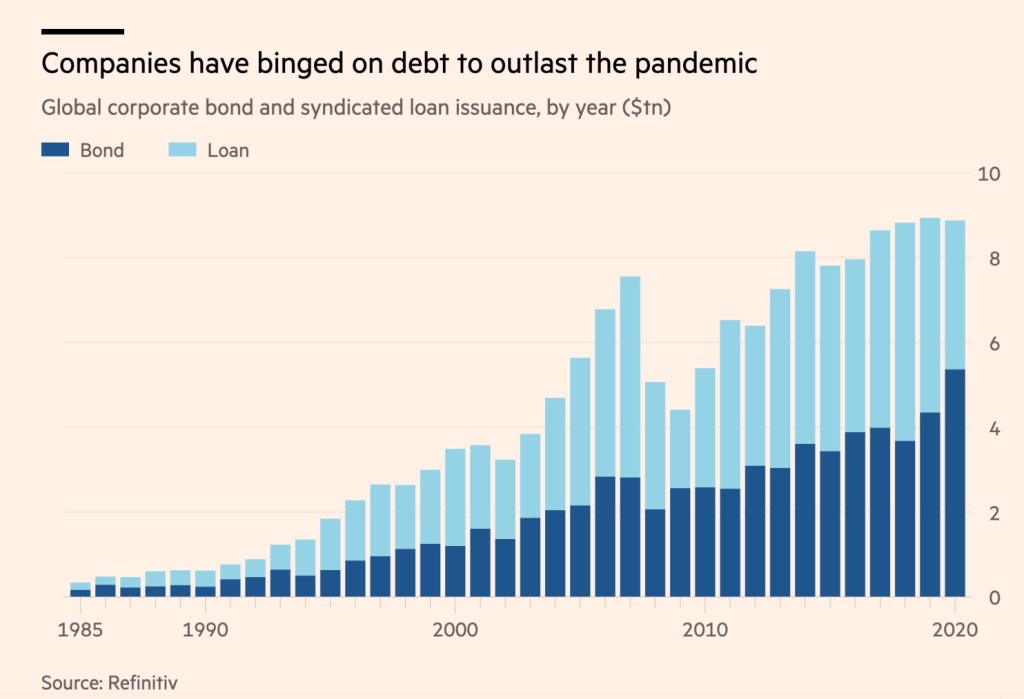

This debt build-up has been mirrored in companies, where corporate treasurers have been quick to load up on what in the past few years has been exceptionally cheap debt through the corporate bond market. Companies went on a borrowing binge in 2020, as they faced into sharp declines in business activity Global corporate debt issuance surged to $5.4tn, a record high and over 20% more than the previous year. Companies also tapped the syndicated loan market for a further $3.5tn. Coupled with the downturn in profitability for much of the corporate world, the borrowing spree has driven up leverage ratios to all-time highs. The ratings agencies view balance sheets as increasingly unstable and forecast a rise in corporate defaults and in the number of “Zombie” companies, where interest payments exceed profits.

The IMF estimates global corporate debt at $20 trillion and has labelled it as a “ticking time bomb”.

This level of indebtedness amplifies any impact we could see from higher rates – a bit like the “away goals” rule in soccer. This is not an environment for aggressive rate hikes!

Higher interest rates can now been seen as a systemicrisk given the abundance of borrowing by both public and private sector. Central banks increasingly take into account the feedback loop from the financial system to the real economy in their policy actions. This underlies the comments from so many central bankers that higher rates are far out on the horizon. As Kristalina Georgieva, Managing Director of the IMF, noted there is a “very, very high probability that they will stay low for quite a long period of time.”

We can also see this in the more flexible attitudes to inflation that many Central banks have taken, and indeed why a number of leading central banks (including the ECB) are reviewing their overall monetary policy framework.

As Central Banks review their policy frameworks and the tools they may select in the medium term, such as asset purchases, forward guidance and macro-prudential policy, interest rates are not on the menu.